“On Finding the Missing Horses”:

A Psychotherapy Case Study

This is the story of one man’s quest to overcome the legacy of being sent away to boarding school.

It has been written at the suggestion of my client, ‘Joe’. It includes his reflections on our work together,

and his description of the dreams that formed the beating heart of the therapy.

Joe has read and approved all that is shared here.

[25-minute read]

Sessions 1-3: Beginning

As a psychotherapist I have a particular interest in trauma, including developmental trauma. In recent years this has led me to undertake specialist training in working with adults who went to boarding school as children.

Boarding school is normalised in British society, and is viewed by most as a high-status privilege. However, the experience of being separated from family and all that is familiar at a young age, and raised largely in care for many years, can result in complex and damaging consequences later in life. Navigating relationships can be especially challenging.

When Joe contacts me, he’s clear that his time at boarding school lies at the core of his difficulties. He had some counselling years ago but somehow it didn’t resolve things for him. Now, having just crashed out of a relationship that he’d really wanted to work, he’s living alone and wants to give counselling another shot. He’s been given my name as a therapist who specialises in working with ex-boarders. We live on opposite sides of the country, so we will meet by online video.

I was left at boarding school aged eight by well-meaning parents: they lived abroad and thought it was best for my education. The abandonment issues this triggered, the pain of feeling you are simply not good enough and you can’t trust anyone ever again, have affected me ever since.

Our first session begins, as therapy often does, by Joe tipping out a bundle of biographical details. He’s now in his sixties, so there’s a lot for us to sift through. He starts with a description of his first night at boarding school, far from home and family. He felt utterly alone and bereft. Decades on, the memory of it is still overwhelming; it remains a vivid, aching, irreparable loss.

By the time Joe was thirteen and finishing prep school, the family had moved back to the UK, and he was given the choice of whether to continue on to another boarding school or not. He said no, and joined a local comprehensive. Life has been challenging ever since. He’s been successful in work but has faced years of “emotional meltdowns”, and several failed long-term relationships.

I knew quite early on that I was different in my capabilities and behaviour to other adults. I struggled to be alone, I was hyper-aware, I had major trust issues, and I would have regular meltdowns. I was not aware of the cause at the time, and I searched for solutions in body/mind activities such as karate, yoga, tai chi, Qigong, meditation and Soto Zen.

The meltdowns eventually subsided around 20 years ago. “But,” Joe says, “I still can’t be fully present with anyone. I just don’t feel whole.”

Throughout the session, Joe talks a lot about his ‘Inner Child’. The concept of a semi-independent, childlike part of the self is a genuinely useful metaphor, but in this case I have a subtle sense of Joe having ‘learned the lingo’ of therapy. Additionally, I have a feeling that Joe is rushing slightly – trying to dive in at the deep end with our work – as if that’s what’s ‘expected’ here. I think about how boarding school is full of rules and regulations… there’s an expectation to conform; no room for the child’s needs or preferences to be heard or attended to.

As Joe speaks, bright and articulate, I take in his overall manner. He is rather softly-spoken (I find myself wondering, where is his edge, his anger?), and absolutely brimful of emotions. Almost every other statement comes with tears. I think to myself, it will help Joe to cope with this work if it is based on choice and steadiness, rather than rules and rushing. So I say I’d really like to work with him, but suggest he takes some time to think about whether he would like to meet again.

After the session, I realise this may well have just sounded like a mealy-mouthed rejection. I worry I may have derailed our work before it’s properly started.

Very concerned that Sarah doesn’t seem very keen. Have I been too open, too emotional? There seems so much to talk about, so many partners and children and so much she needs to understand. Or is she just being polite and she doesn’t like me? Or just being professional and I am rushing.

I am relieved and pleased when Joe emails to say he’s decided to continue with our sessions – I like him, and am looking forward to our next meeting.

————————————–

The following session, Joe begins by showing me a photo of himself, aged 7, just before he started boarding: he looks so innocent! The reality, however, was more complex. Little Joe had been very close to Mum – they shared a love of sport – but Dad was an angry alcoholic bully, violent and threatening. Home felt unsafe. Mealtimes were a “battlefield”. We note, maybe that’s where Joe started learning to fit in with whatever authorities required.

There was another learning, too, from Dad’s anger: “I don’t allow anger in myself – it’s explosive”. I am always interested in what happens when the energy of anger is totally suppressed. It can, of course, be volatile; but without access to our internal ‘spark’, we can lose the engine that powers us forwards in life.

At boarding school, Joe excelled at sport. He became one of the bullies, hitting anyone who broke the rules. This lasted until his final two terms, when he was made Head Boy. Then, he became gentle, even protective. Under his regime, bullying was forbidden, and new boys were allowed to keep their teddies beyond the first night. I say, it’s as if he stopped needing to bully others when he was no longer vulnerable himself. Joe isn’t sure; he’s simply aware of pushing away his sad/angry Child-self.

With anger disallowed, and sadness pushed away, I am not surprised Joe doesn’t feel whole.

I’m still just filling in details. I know that it will start to get difficult; I both want this to happen and don’t want it to happen. Am just trying to be honest, and hoping that is somehow going to make everything ok.

Joe says lately, he’s been really struggling with aloneness. I recall how engulfed by aloneness he felt on his first night at boarding school. This ‘aliveness’ of the past is a common feature of traumatic memories that have not been fully processed.

He’s also been dissociating a lot: he describes it as ‘killing time in his head’, away from his body, unable to stay fully present. He’s ashamed of it, even though dissociation is a natural way to escape from overwhelm and pain.

Joe recounts wetting the bed in that first week at boarding school, and the shame of the dark sheet. And darker still: memories of sexual abuse, from a creepy headmaster who touched him inappropriately, and watched him bathe. Joe relates this quite factually but I am acutely aware of what a violation it was, what a terrible betrayal of trust.

Reading about my old headmaster now, I feel anger! I couldn’t feel that then. It is such a hideous abuse of a child.

Joe speaks more about the meltdowns he experienced for years, from his early teens until his early 40s, describing them as an “overflowing lake of sadness”.

I now realise, writing after our sessions, that the meltdowns were caused by my child not being able to cope with emotions, and the abandonment trauma that would be triggered by many day-to-day experiences. But at the time of this session I didn’t know that, so I was circling around trying to understand and describe it. They didn’t seem to have any rationale or coherence.

With yet more shame, Joe mentions that he has been spending a lot of time watching BDSM / masochistic porn; his fantasies are about being ‘punished’.

The porn is, although shameful, very relevant – both the almost addictive nature of watching porn, and the type of porn. I watched porn to escape into another world. It’s very like choosing to disassociate rather than that happening unconsciously and out of control. I was really struggling to be by myself, with myself, my desperate abandoned Child. I subconsciously knew that if I spent too much time as my Child I would sink under a wave, a tsunami of terrors. I didn’t have the skillset necessary to just be. Watching porn was a ‘bad coping mechanism’ or whatever the correct counselling terminology is. The sado-masochism almost goes without saying. I wanted to be punished and thought I deserved to be. I think this is almost a cliché for public/boarding school boys, who then become adults in age but not in actuality.

Joe is ashamed of all his emotions – and of dissociating from them. He is ashamed of himself, his past, and his desires. Internal judgement and self-criticism seep from every pore; he feels ‘bad-at-the-core’.

Nick Duffell explains this is common amongst ex-boarders. There is a terrible ‘double-bind’ that a child finds himself in when he is first left alone at school, flooded with feelings of loss, fear and helplessness. “If [Mummy and Daddy] love me, why did they send me away? …If they don’t really love me, it must be because I am bad. If they do, and I feel like this, it must be because I am bad.”1

I am aware that many of Joe’s conscious thoughts are playing on repeat – a lifelong negative, self-critical loop. I would like to open the door to alternative ways of understanding things, so I mention that if he has any dreams that feel significant, I’d be interested to hear them.

At this stage my primary role is to be a safe container for all the thoughts and emotions; to absorb what is both said and not said, and gradually reflect it back to Joe in a way that can be thought about and remembered. I still don’t know exactly where or how things may progress.

Sessions 4-5: Movement

Joe describes having no sense of any real, authentic self. He says he never showed what he disliked, either at home or at school. He’s happy in a ‘role’, e.g. being a dad, or at work; but otherwise, he shapes himself to others: “I just don’t know who I am!”

I have been thinking between sessions about how different Joe is from other ex-boarders I’ve met. He was highly successful at his prep school – captain of all the sports teams, and eventually Head Boy. But he doesn’t have the public-school swagger, the polished veneer of self-confidence, that many other ex-boarders have.

Duffell talks about the ‘strategic survival personality’ that a child often develops in an institution like boarding school: a way of navigating the system by first complying with and then buying into it. There is often a total dissociation from their own vulnerability, and a disdain for vulnerability in others. And a basic mistrust of relationships, because everyone will let you down. The typical ex-boarder can look self-assured, affable and at ease in company, but internally plays a careful, wary ‘game of one’.

I muse out loud to Joe that he had the first half of the boarding school process (age 8-13), but missed out on the second half (13-18). It’s as if he successfully suppressed his ‘real’ self, but never fully consolidated a ‘false’ self to wall off his vulnerable Child; his survival personality managed prep school brilliantly, but then collapsed. He’s been left with a bundle of unknowns about himself.

At this point, Joe brings his first dream. He recounts the following:

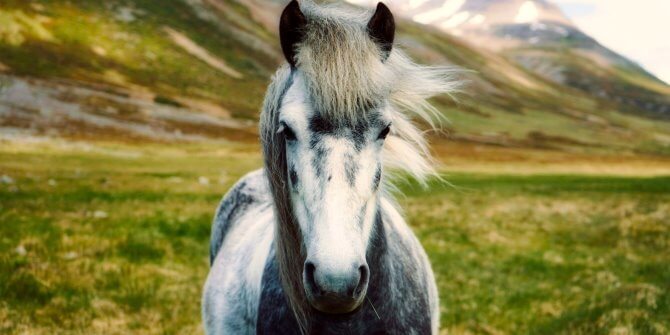

I am out in the countryside, it’s a warm sunny day and I’m with my daughter and my beloved dog. We see that the fence to the ponies’ field is broken and some of the ponies have escaped, and we go looking for them. The countryside is hilly and undulating but there is no rush or panic, and we sort of know that we will eventually find them.

I comment on the parallels with our work, here: a search, with a trusted companion, for ‘something missing’; an up-and-down terrain. We note the interesting dream-certainty that his quest will be fruitful.

Internally, I’m thinking that Joe’s unconscious mind seems to be settling in with therapy: it says there is no rush or panic, and it has confidence in the outcome. Hopefully we are over the jarring impact of my initial clumsiness.

I am also thinking about how the horse exists in multiple cultures and mythologies as a metaphor for the power, instinct and wildness of the psyche. Its unbridled passion is a vivid contrast to boarding school’s ‘rational man’ project. In Jungian psychology the horse symbolises strength and speed, and the ability to move forwards in life. It is seen as a bridge to the unconscious, and particularly the ‘shadow self’ – the part of us containing powerful inner drives, such as anger or hatred, that we would rather disown but which might be helpful to us if we can ‘saddle and ride’ them.

I suggest to Joe, perhaps our task here is to find the ‘horses of his soul’ – that ‘missing’ part of him which is wild, free, instinctual, and alive.

I’ve also been sitting with Joe’s earlier comment about never showing what he disliked when he was growing up. I’m really curious about this. Our likes and dislikes are a key part of our sense of self, of who we are in the world. We often form identities and communities around these things. Discovering personal preferences is a significant part of a child’s development – and much of it involves identifying dislikes. Even a tiny baby will instinctively spit out what tastes bad.

I suggest that Joe might think over the coming week about what he dislikes, now.

Sarah’s question of what I dislike really intrigues me. I spend the week pondering this so that I will have answers. But also it seems easier somehow, I can include more frivolous things than if I were trying to find my likes.

After the session, the dream-horses run around my mind. I reflect on the fact they have “escaped”. Joy Schaverien writes about the sense of ‘captivity’ experienced by a child left at boarding school. No matter how lovely the surroundings, there is no escape from them, no returning home – so for the child it feels like an imprisonment.2 I am rather delighted that Joe’s horses have made a break for freedom.

My dreams are becoming very vivid. I wake up thinking about them and seem to know immediately if that was a ‘Sarah dream’. ‘Sarah dreams’ are alive and can be recalled but also seem to go to my very core. I am learning to look inwards through my dreams. It’s not as scary as discussing emotions.

————————————–

The following week, Joe announces, with some humour, that he dislikes getting out of bed in the morning: “it’s too hard to be me!”. And, though he finds it an odd thing, he notes that he dislikes his hand being in cold dishwater. I ask what his body knows about that sensation. Joe recalls, to his surprise, a quite unpleasant memory of his dad throwing him into a cold swimming pool when he was little – suddenly the dislike of the cold dishwater makes sense.

I don’t pursue this memory further; the most important thing for now is that it brings Joe’s body into our work, as a reliable interlocutor.

He relates two new dreams:

I am with my daughter once again. I feel relaxed in her company. We are sitting on the sofa and we are trying to complete a school-related task, some homework which we often do together, particularly maths, but this time we just can’t do it. It’s impossible, but somehow that’s OK.

I am at a football stadium. It’s the Emirates and I’m with the Arsenal manager Mikel Arteta, and we appear to be on first name terms, almost friends. There’s going to be a big game that evening. But instead of a match today, Mikel turns to me and says he wants there to be bonfires on the pitch. I laugh at him and try to persuade him otherwise. Lots of people are going to be turning up and they will definitely want to watch football, I tell him. But he is insistent and suddenly the bonfires have started and I slowly realise that they are made of my belongings, my family photos. I am shocked.

I say, both of these seem strongly related to our sessions. In the first, two people in relaxed company (like he and I) work together on an “impossible task”, but somehow that’s OK. The second is more disturbing: the person with Joe starts out “almost a friend” but then insists something shocking must happen. The destruction of all he holds dear, orchestrated by a trusted sport-loving person, sounds awfully like little Joe being sent away to boarding school by his seemingly dependable, friendly mother. The dream points to a real fear about our sessions here: perhaps the ‘manager’/mother/me cannot be trusted.

There could be another layer of meaning to the dream-bonfires, too. In alchemy, fire is seen as the primary agent of transformation, capable of changing substances and bringing about new forms. Joe says this week, he’s had the first hints of it being “OK to be me”; “OK to stop running”. Could we be seeing the first signs of change?

I am beginning to have some faith in the process. I feel less panicky. I have never worked with dreams before but they have helped me to have more trust in Sarah. But being able to see myself more clearly is a double-edged sword. There’s lots of things not to like about myself.

Sessions 6-7: Stagnation

Our glimpse of change turns out to be short-lived: we enter a period of complete stuckness. Joe talks about having “absolutely no self-esteem”, outside of his job. This is perhaps no surprise – it’s hard for genuine self-esteem to flourish in an abandoned child. Joe says it’s like he’s never fully developed a proper adult self. He’s stuck at age 8, with overwhelming sadness. “I can’t go back and comfort my Child – there’s no adult to do that.”

I’m starting to worry that this isn’t working and I can’t see an ending. I’m starting to see more and more of my abandoned Child, and he can’t cope. I seem to have no adult. Sarah’s previous comment about my ‘partial’ boarding school experience really resonates. I appear to be just a child, a lost boy, a Peter Pan who can never grow up.

A week later, he’s still utterly desolate, and almost drowning in loneliness: “Nothing really helps”, he says. Years of Zen, Qigong and other bodymind practices feels like it was all just “playing”. He thinks about the teenage surety of his now-adult son, and envies it terribly. Joe can’t imagine ever feeling confident or sure of himself.

Joe’s despair in these last two sessions has been difficult for me to sit with. I cast around for reflections or interpretations that might help us move forwards, without success.

I’m desperate to hook up again with a partner, being on my own is so hard. My loneliness is heart-rending and I’m not sure how much more I can take.

Then – and I don’t recall how it came up – Joe remarks on a previous brief experience of couples therapy. He mentions “the choice-point that exists once all the shit’s tipped out: will you stay together or not?”

This strikes me as a particularly apt metaphor for our work here, pointing to Joe’s adult and Child, and their long struggle to co-exist. His internal couple has ‘tipped all the shit out’ in our sessions and is now at a choice-point. I ask, if our work here is about Joe’s relationship with himself, what’s he choosing?

Joe is clear and firm: “To make it work”.

Sarah’s comments on the couple’s therapy hit home. I hadn’t thought about connecting it to myself, but I am at that point where I can see all the crap more clearly and now I have to stick with it and push on. Time to be an adult.

Sessions 8-9: Stabilisation

Joe’s descriptions of daily life this week point to a growing sense of balance between his adult and Child. The internal couple is ‘taking turns’ more fairly, with the adult more active and present. He is able to start looking more calmly on the interplay between these two parts of himself.

He reflects that both parts have always coexisted quite well when he’s being a dad to young kids. His Child keeps him playful, fresh and energised (without its hurt or fearful side), while his adult is capable and confident (without being rigid or humourless). This is a really important observation, as it indicates that some part of Joe already knows what a well-balanced self looks and feels like. This means that the process of integration will not need to be an entirely new learning; rather, it can be a natural expansion from one part of his life to a wider field.

His adult has been most notably absent in relationships. His ex sometimes asked him to talk about their relationship, but he had no words. I say, no-one ever helped him, as a child, to find words for his inner life or emotions.

Joe describes his anger at his parents, for sending him away! – and, with some surprise, he realises there is also long-held anger at himself, for somehow “not getting it right”. I observe, that anger got expressed towards the other kids at school when he bullied them. Then, from the moment he was made Head Boy, it was disowned.

I explain how anger can be a stabilising force against overwhelm and collapse: mobilising survival instincts, providing motivation for change, strengthening and energising with its shot of adrenaline. Joe says, he’s never really thought much about his Child’s anger before, but he notices that today, for the first time, he’s been able to talk for the whole session about his Child without getting overwhelmed.

We may have found a route through terrain that was previously impassable.

I realised that anger was a key to the door to my boarding school Child. It was like I could enter the boarding school with my coat of anger on and not be overwhelmed by my abandonment, my sadness and my despair. I could get close to my Child with my anger coat.

Sessions 10-12: Transformation

Joe has been thinking about anger. If he tries to access it in Qigong exercises, it just feels like “play-acting”. But he has “real anger” – with whirling thoughts! – at “people who don’t do what they should, like football referees, or Trump”.

I think inwardly about the parents who sent him away, instead of keeping him safe and protected at home as they ‘should’ have done. But it seems more important to stay with the emotion of this ‘real anger’. So I ask, what does Joe notice in his body while his mind is whirling? – what are the sensations?

He detects an “agitation” in his legs. He considers this quite random. But Eugene Gendlin suggests that the bodily ‘felt-sense’ of something contains its own wisdom; its own images, memories, and emotions. Tuning in to these knowings-of-the-body can move the psyche forwards in a transformative way.3

I ask if Joe can sit with the agitation and see what else he notices about it, and he realises he wants to kick! I invite him to allow the kicking… and a body-memory emerges, of being held-down. It comes with an image of his dad, very large, and Joe screaming. He feels “about 2, or 3, or 4 years old” – it’s long before boarding school. There’s a sense of powerlessness; frustration; fury. This is a really visceral remembering. We let it sink in for a minute.

I comment, bullying at school would have redressed this feeling: it was a power-over-others. Joe nods, and adds insightfully that his current job, in Quality Control, does that too.

Joe reflects more generally on things being held-down, and the way his bodymind practices have effectively held down his emotions by training him to be present-in-the-moment. Suddenly, it feels like the practices themselves aren’t quite who Joe is: maybe it’s the holding-down-of-emotions that has been a truer, deeper statement of who he is.

I think to myself about a horse’s powerful kick – such a vital part of its protective arsenal. Now that Joe’s kick has been released, perhaps he can access his full power, and begin to free himself.

Something has definitely shifted, and I have the most powerful dream [the following week] to confirm this:

I am driving in my car. I turn into a courtyard area that consists of several parking spaces with a number of garages. I pull in to park and as I do so I notice this young woman standing in front of one of the garages on the left of my car. She is looking directly at me and our eyes lock; we connect and I am instantly filled with the most amazing peace. I park the car all the time looking at her. She has such presence. I don’t get out. Somehow there is nothing that needs to be said. Nothing needs to be done. She knows everything about me – she always has done. She has such calm that I am filled with it. She has been waiting for me. She has a David-Bowie ‘Aladdin Sane’ hairstyle but in blonde. Her presence is unworldly.

Joe and the dream-woman are clearly interchangeable: she knows everything about him; he is imbued with her calm. I ask for Joe’s associations with David Bowie – he says, the music represents his early teens, around age thirteen.

Our teenage years are the time we throw off the compliance of our younger years, delighting in rebellion, and testing out new ways of being in the world. At thirteen, Joe said “no” to boarding school – a very healthy revolt. But it was also when he became ‘a lad, insane’, plagued by meltdowns he didn’t understand, unable to settle into his emerging adult self with any confidence.

Bowie’s demeanour in TV interviews as Aladdin Sane suggests a different combination. He is clearly rebelling, against the rules of polite society. But he’s also strikingly self-assured and at ease in his own skin. The dream-woman embodies this blend of confident rebellion and calm poise.

This dream is the turning point for me. I am able to fully realise my adult. I no longer live in fear.

Joe says, it feels like his dream has introduced him to his ‘inner female spirit guide’. I think about Carl Jung’s concept of the anima/animus – the complementary-gender archetype within the psyche. Acknowledgment and integration of the anima/animus is seen as a crucial step in the journey towards self-discovery, balance and wholeness. For a man, integrating the anima can signal a greater capacity for emotional depth, increased creativity and intuition, and enhanced relationships.4

I go out to garden and as I am weeding and deadheading, the silence of my mind allows feelings to flow out as if I am a well, a spring. It is as if I am truly alive for the first time.

I try out my new adult, what does he like? – I’m not sure, but now there is a wealth of possibilities. I cook an Arabic meal for myself, reveling in my new confidence, composure and just bog-standard normality!

Joe has moved on from noticing his dislikes, to exploring what he does like – with genuine teenage enthusiasm and vigour. He describes this new adult self as being “just born last week!” He is not dissociating. He’s not using porn. It all feels very natural.

I offer an image of ‘Russian dolls’: when properly stacked, the adult contains the Child inside. No part is excluded or abandoned. No part is left empty. There is a wholeness.

I truly experience Sarah’s words of being a complete adult and my Child is just a small ‘Russian doll’ inside. My emotions no longer engulf me but merely lap at my ankles.

Joe brings a new dream:

I am standing in my hallway and I hear noises in my porch. I open the front door to see it’s filled with hundreds of parcels. Like the scene with the letters coming out of the chimney in Harry Potter.

We note together, so many magical parcels to open / things to be discovered, about his new, whole, adult self!

I am a changed person. At tea-break at work I have a bloke-ish conversation about car tyres without fear that I’m going to be ‘found out’, that something might trigger my child’s emotions. It’s so easy and normal. No need to run and hide away.

Sessions 13-14: Integration & Ending

It’s been four weeks since our previous session, due to my holidays and then Joe’s. He describes a life transformed. He’s back with his former partner, no longer running from emotion or from the future. He never used to be able to plan anything; now, he’s thinking about both marriage and retirement. Joe feels able to trust his ‘larger self’, including his dreams and his body. And, to his delight and amazement, he finds that he likes himself!

He’s had another dream:

I am shitting copiously, flooding the toilet with endless turds. Then I am having dinner with my childhood family sat around the table – and then suddenly vomiting up more shit over the table as I rush out. It’s horrible, disgusting. Then I am upstairs in my bedroom crying and comforting my Child, who is in my arms. My elder sister is there and says matter-of-factly that I need more counselling.

This dream points graphically to the deep purging that has taken place of all that was horrible and disgusting in Joe’s past, and his psyche. It shows him finally able to cry and be vulnerable, as an adult. And that adult instinctively offers the longed-for comfort to his traumatised Child – something Joe had said just a few months ago was impossible.

I’m aware of Joe’s sister, in the dream, suggesting he needs more counselling. I ask, what does he think? He explains, his sister is someone who always related to his Child. Now he’s a fully-fledged adult, her advice no longer feels relevant. “I’m not sure there’s any more ‘shit’ that needs to come out”.

I check in with myself about this. How close might we be to finishing our work together? I would have expected some of the issues Joe brought in our early sessions to need further exploration, but they don’t seem relevant now. I pay special attention to the ‘unspoken edges’ of the conversation as we talk, but I don’t get any sense of things being avoided or forgotten. The changes Joe has been describing seem well-rooted and healthy; the shame that had so profoundly stained his sense of self has melted away. Coming to an ending feels appropriate.

For longer therapeutic relationships, endings might be planned over anything from a few weeks to several months. With a short piece of work like this, it’s different – in fact, many important parts of an ending process have already been unfolding in this session. Joe has been talking about his plans for the future, how prepared he feels, and what is still a ‘work in progress’ for him. We have spent much of today celebrating the total transformation of who he is now compared to who he was when we started. We agree to meet for one last session.

————————————–

In our final meeting, Joe reports feeling “stable and steady” on his own feet. He still has the same ‘tendencies’ as before (e.g. what he enjoys sexually, or comfort-eating), but they are “no longer compulsions, simply preferences”. Gardening, which was previously just an escape from distress, is now a wholesome enjoyment.

Joe’s relationships with his children are deepening, and he’s now planning to cultivate a circle of close friends (something he’s not had before).

To be able to live without the anxiety generated by being an abandoned child is delightful. Suddenly a whole new life is possible, of being able to connect with myself and with others.

His new ability to plan and think about the future reminds me of the horses in his first dream, and their archetypal symbolism of moving forwards in life. I have a sense of Joe having harnessed the horses’ strength, power and freedom, integrating them fully into his psyche and his self-image.

I’m conscious of the unusual brevity of my work with Joe. As his story unfolded in our early sessions, I anticipated we might be working together for many months, even years. The remarkable pace of change has been unexpected – and is not my doing.

I tell Joe that I think his many years of bodymind practices, his long cultivation of openness and insight, have played a huge role in our work. In particular, they have helped with his consolidation of all the changes – of meeting, understanding, absorbing, and utilising inner shifts. I would normally expect to spend a good deal of time working with someone on all this, but Joe has been able to do it intuitively, and comprehensively, by himself.

There’s a light-heartedness to this final session. Plenty of smiles and humour. Also huge gratitude from Joe, which I find difficult to accept graciously.

As I reflect on our work together, what really stands out for me are the rich knowings of Joe’s dreams and body. Within them was a tremendous powerhouse of unconscious understandings, and creative pathways towards change. I recall Johanson and Kurtz’s description of the psychotherapist’s role as being that of a midwife: “When the baby is born, there is no question to whom it belongs”.5

A Post Script

It is at the end of our final session when Joe suggests I might write a case study on our work together.

I’d been in a boarding-school-survivors Zoom meeting a while ago, and someone said to me they were so lonely. I felt, and knew, the depth of his loneliness – it touched my being. But as I was still childlike myself, I was unable to do anything for him. He stopped attending shortly after that.

If the story of my therapy can help other boarding school survivors in any way, it would be wonderful.

This is an incredibly generous offer… but there’s a lot to think through. First and foremost, I am mindful of the potential effect on Joe. What might it be like for him to receive so much information on my internal thoughts? What if some of my ideas or reflections jar with his experience? Might the picking-apart of the therapeutic process dull the impact it’s had on him? What if his enthusiasm for a case study wanes, but he feels he must continue in order to please me?

On the practical side, where and how could such a study be shared? How much should be anonymised? My instinct is that as it’s Joe’s idea, the writing should be collaborative in some way – but how might we construct and edit a narrative together?

We agree to meet again and discuss the idea in more detail. Joe brings two dreams:

I am an adult. I’m in a building and there are zombies crowding round outside – a bit like in the pub scene in “Shaun of the Dead”. I take my ‘work’ (a delicate bowl I’ve made) out to show them; they are quite uninterested, and unable to understand or appreciate the bowl.

I am a child. I’m a strong swimmer, almost fish-like, out in the sea, helping other struggling children to get to the shore. There are adults standing talking in the waves, oblivious to the children and their struggles.

We observe that the first dream seems to relate to Joe’s fears about the case study: that it risks being either ‘ripped apart’ (zombie-style), or met with disinterest and lack of appreciation. The second seems to be about his hopes: that the story of his now-strong-and-confident Child will be able to help other (ex-boarder) ‘children floundering at sea’, despite adults who continue to ignore the problem.

I have my own fears, too. In many ways there is an incompleteness to my work with Joe. There are many blank details about his life; many issues raised early on (such as sexual abuse, and the feeling of deserving-punishment) that we never delved into. I worry that readers will think me remiss for having left so much unexplored. I have to trust that the ‘intuitive shorthand’ that seemed to characterise our work together was accurate; that we somehow cut straight to the heart of Joe’s issues; that ‘more’ would not necessarily have been ‘better’.

Over the course of three further meetings, and several iterations of our joint document, we address the practical issues, and maintain a close eye on Joe’s feelings about the project.

Reading Sarah’s case study has been, surprisingly, not triggering, but almost – struggling for the right word here – comforting?

To be so completely heard is heartwarming.

In the end, we agree we are both OK to move ahead. We will release the work into the world, and let it speak for itself.

References

- Nick Duffell (2016) Trauma, Abandonment and Privilege: A Guide to Therapeutic Work with Boarding School Survivors. Abingdon and New York: Routledge

- Joy Schaverien (2015) Boarding School Syndrome: The Psychological Trauma of the Privileged Child. London and New York: Routledge

- Eugene T. Gendlin (1996) Focusing-Oriented Psychotherapy. The Guilford Press

- C. G. Jung (1968) The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Routledge

- Greg Johanson & Ron Kurtz (1991) Grace Unfolding. Bell Tower

Share This Case Study:

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Sarah Hamilton is a psychotherapist, counsellor and writer based in the Welsh borders.

She sees clients at her private clinic in Hay-on-Wye, and also offers online therapy by secure video link.

Want help dealing with boarding school issues?

The following organisations offer a range of workshops, support groups and other resources for ex-boarders.